Duke Shares Strategies for a Structured Capital Approval Process

June 2, 2014

Duke University Health System’s rigorous approval process for $1 million-plus capital requests has served the health system well for more than a decade.

Fourteen years ago, Duke University Health System, in Durham, N.C., implemented a rigorous capital approval process for $1 million-plus expenditures that allows the three-hospital system to make strategic investments and monitor the effectiveness of those decisions over time. “The rigor in the process helps us make sure we are making good decisions, especially when we are looking to get the most bang for our buck from our capital investments,” says Krista Lutz Harris, MHA, senior director, finance.

The core of the capital approval process has remained the same over the years, even as Duke moved from a paper-based system to a more automated process that interfaces with its third- party financial platform eight years ago.

Creating a Systemwide Schedule

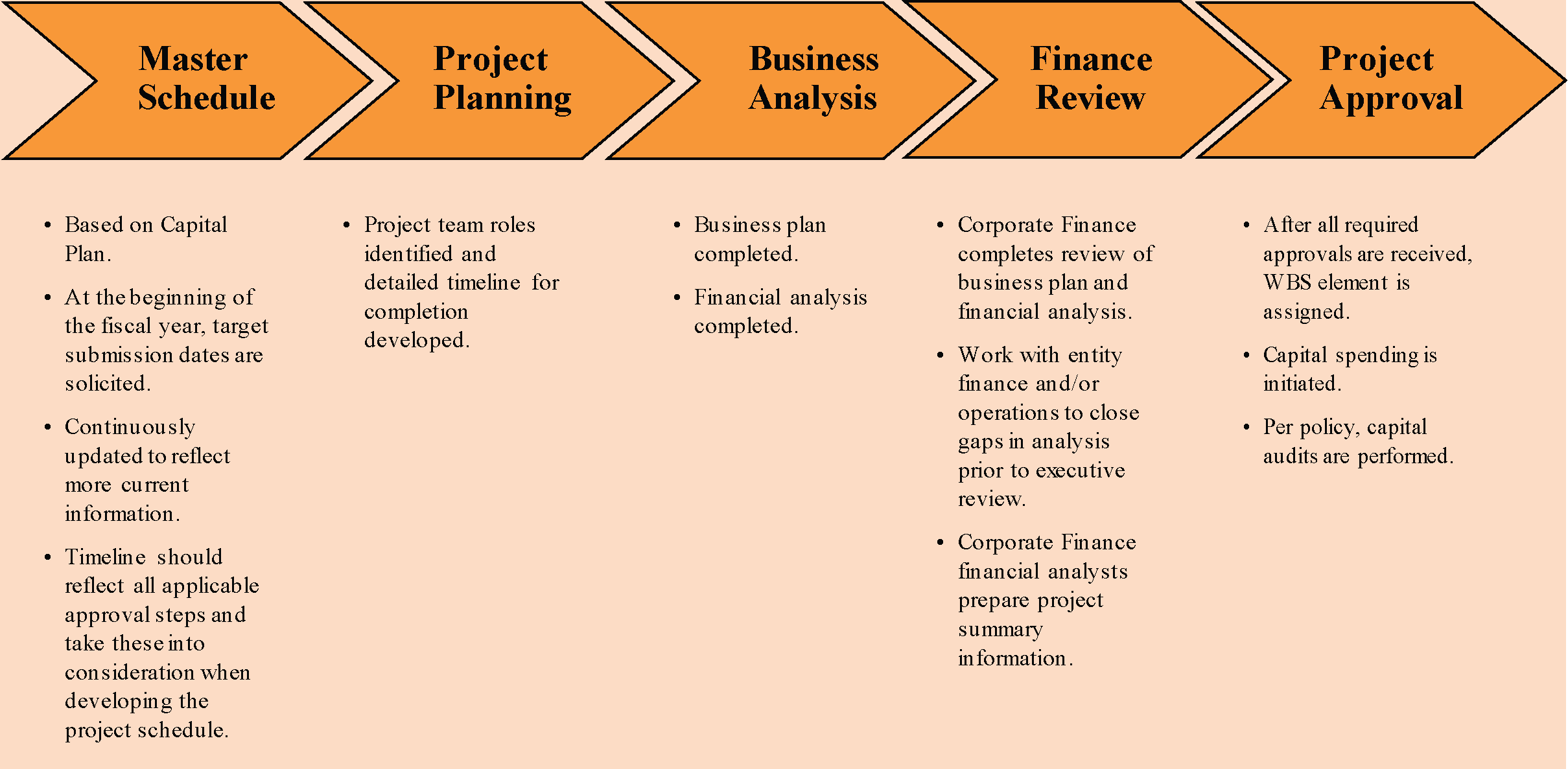

At the beginning of each fiscal year in July, corporate finance leaders at Duke review the system’s $1 billion, five-year capital plan and develop a master schedule for the next 12 months. This master schedule includes a timeline of all capital projects with investments of $1 million or more. “It helps us determine the heavier times of the year in the capital approval process,” Harris says.

To decide where each capital project fits in this master schedule, corporate finance leaders work with the project champions who have operational responsibility for the projects. The scheduling may reflect certificate of need application deadlines, planning time, or other factors. Once every three weeks, corporate finance leaders and entity hospital CFOs meet to update the master schedule, based on the projects’ progress.

Developing Business Plans

Duke’s corporate finance team requires business plans for any capital request of $1 million or more. To help project champions develop their business plans, corporate finance leaders maintain two templates: one for clinical projects and one for nonclinical projects. The clinical project template contains three main parts:

- Operations, where project champions can include an internal assessment, project overview and justification, and implementation plan

- External environment, which requests data on market demographics, competitors, volume projections, and payer mix

- Finance, which requests forecasts pulled from Duke’s third-party financial platform as well as revenues and expenses, capital detail, and ROI calculations (including net present value and modified internal rate of return)

Unlike the clinical project template, the non- clinical project template does not request information on incremental volume or revenue justifications, Harris says. The non-clinical project template also does not include an environmental assessment.

“The business plan templates help project champions look at the impact of a project from several different angles,” Harris says. For the internal assessment, for example, a project champion might provide an outline of current service lines, payer mix, patient demographics, and potential profitability. “We want people to justify the project, so we ask for volume projections, referral sources, and alternatives that have been considered—and ask why these other options are not as viable as the proposed project,” she says.

Requiring this level of financial analysis helps ensure that project champions are doing their due diligence. “The templates also provide the entities with a good idea of how we are going to evaluate a project,” Harris says.

In many cases, corporate finance leaders will review draft business plans and work with the entity hospitals during the planning stages, Harris says. This helps project champions develop more effective plans.

“Many of us in corporate finance have seen similar projects at other hospitals, and know the questions that senior leadership tends to ask about these projects,” Harris says. “By being involved early on, we can guide people in what they need to be successful ahead of time.”

After business plans are submitted, corporate finance typically reviews and approves the plans in about two weeks before they send them through the automated approval process in their financial platform.

Auditing Investments Over Time

To monitor the effectiveness of their strategic capital investments, Harris and other members of Duke’s corporate finance team conduct about seven to 10 capital audits of approved projects each year. The purpose of each audit is to provide senior management with a report comparing the actual results of a project to the original projections.

Harris believes these audits are critical to continuously assessing the capital approval process and the assumptions used to develop business plans. The audits also help the finance team verify that the entity hospitals are following Duke’s corporate policies and procedures.

Initially, Duke’s corporate finance team completed audits for all capital projects of $1 million or more. “But we found that if the project didn’t have incremental volume and it was more of a replacement item or system implementation, there wasn’t a lot of meat to the audit,” Harris says.

Today, Duke only audits capital projects between $1 million and $5 million if they add incremental volume or generate revenue. Corporate finance still audits all capital projects of $5 million or more and reports the findings back to the board of directors, which approves these larger investments.

Corporate finance conducts these audits after a capital project has completed a full fiscal year of operations. For each audit, the corporate finance team supplies the entity hospitals with reports that detail the actual capital expenditure for the project. Then, corporate finance provides the entity finance team with a Microsoft Word™ based audit template so that entity finance leaders can provide the variance analysis on expenses and explanations for the cause of the variance.

The template also helps the entity finance leaders report projected versus actual volume so they can conduct a variance analysis and make any adjustments needed (such as scaling back expenses) to make the project profitable. The entity finance team sends the Word template back to corporate finance, which then prepares a standardized PowerPoint™ presentation on the audit results for Duke’s senior leaders (and board if the project is $5 million or more).

Early on, one of the most challenging aspects of conducting the audits was determining how to measure the actual versus projected volume, expenses, and other data because leaders were often uncertain how the original data was pulled—particularly if the project champion left the system, Harris says. To fix this problem, leaders added more structure to the business plan template. Today, project champions are required to explain how they calculated their projections in the business plan so others can replicate the calculations at audit time.

Learning from Duke

Harris offers the following advice to other healthcare organizations that want to add more rigor to their capital approval process.

Enlist senior leadership in helping educate others on the new capital approval process. “We had moved from a loose capital approval process, and the biggest challenge early on was getting people to embrace the change,” Harris says. “Senior leader support helped solidify the process and get buy-in from the organization.”

Develop a “dog and pony show.” Having a ready- made slide presentation on the capital approval process made it easier for Harris and her team to take advantage of last-minute opportunities, such as department meetings, to educate leaders across the system on the new process, Harris says.

Develop templates. Duke’s business plan template helps project champions and those approving the requests (including board members and other senior leaders) to better understand the requirements, Harris says. The capital project audit template also helps establish more accountability among project champions and corporate and entity finance leaders.

Finally, all finance staff should understand the capital approval process for every size request. As discussed in the sidebar below, Duke has a separate process for capital requests less than $1 million. As Harris says, “your staff should be as educated as the lead person for capital because they can be the biggest advocate for the process.”

A Different Process for Smaller Requests

For capital requests less than $1 million, Duke University Health System’s process is primarily handled at the hospital level, says Krista Lutz Harris, senior director, finance. Each hospital’s capital steering committee prioritizes each request for the upcoming fiscal year’s capital pool. When the fiscal year begins in July, the highest-priority requests are routed for approval. Corporate finance also monitors this process and keeps it moving.

Over the past 14 years, the capital process at Duke has evolved, Harris says.

Today, corporate finance maintains four distinct capital pools for clinical, diagnostic, facilities, and information systems requests less than $1 million, although that was not always the case.

“In the early stages, we did not have a separate capital pool allocated for diagnostics, including radiology and lab. Instead, these would be funded by a hospital’s clinical pool. But because we have a central management group over the diagnostic area, it made the most sense to give each group a pool of dollars for routine items that would need to be replaced on an annual basis.” By allowing the capital process to be flexible, leaders at Duke can continue to make the most informed investment decisions for the organization, Harris says.

A Different Process for Smaller Requests

For capital requests less than $1 million, Duke University Health System’s process is primarily handled at the hospital level, says Krista Lutz Harris, senior director, finance. Each hospital’s capital steering committee prioritizes each request for the upcoming fiscal year’s capital pool. When the fiscal year begins in July, the highest-priority requests are routed for approval. Corporate finance also monitors this process and keeps it moving.

Over the past 14 years, the capital process at Duke has evolved, Harris says.

Today, corporate finance maintains four distinct capital pools for clinical, diagnostic, facilities, and information systems requests less than $1 million, although that was not always the case.

“In the early stages, we did not have a separate capital pool allocated for diagnostics, including radiology and lab. Instead, these would be funded by a hospital’s clinical pool. But because we have a central management group over the diagnostic area, it made the most sense to give each group a pool of dollars for routine items that would need to be replaced on an annual basis.” By allowing the capital process to be flexible, leaders at Duke can continue to make the most informed investment decisions for the organization, Harris says.

This article is based on an interview and a presentation at the Strata Decision Summit in Chicago in October 2013.