Infusing the Healthcare Capital Review Process with Discipline

May 1, 2015

During the past four years, leaders at Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City have revamped their capital allocation process. Their goal was to ensure that funding decisions are made more objectively and strategically across the not-for-profit health system, which comprises 22 hospitals, a mature health plan, and approximately 1,200 employed physicians. By providing clinical and operational leaders with better guidelines, tools, and support, Intermountain’s finance team has helped infuse the organization’s capital process with greater discipline and enhanced transparency.

Driving this push for enhanced discipline and revised methodologies is Intermountain’s philosophy of shared accountability, which includes aligning incentives for everyone who has a stake in health care. Although strong analytical practices certainly are present in the industry, many health systems around the country still are using traditional, volume-based methodologies to prioritize and vet their capital investments. Such practices are inadequate for healthcare organizations weighing long-range investments that could serve as the foundation for providing true value under population health management. Intermountain’s experience points to strategies that leaders can use to help their organizations make wiser investments that are better aligned to improve quality and reduce cost.

Look Outside the Industry

Recognizing that capital decisions are not discrete events but strategic choices with long-term consequences that can span decades, Intermountain’s leaders set out to make their capital decision-making process more progressive and objective, borrowing lessons learned from other organizations.

In 2011, Intermountain’s finance team interviewed their peers at a dozen AA-rated, not-for-profit health systems to uncover best practices in project analysis, oversight, and other aspects of capital planning. Intermountain’s finance team noted many strong practices but gained the greatest insights by interviewing leaders in industries outside of health care, including technology, hospitality, consumer products, and mining.

Certain themes arose during those discussions. In particular, non-healthcare industries tend to have more objective metrics and are less prone to basing capital decisions on emotional considerations and preconceptions. Also, the level of justification for a capital investment (both in terms of analytical rigor and comprehensive due diligence) is more pronounced in non-healthcare organizations. Moreover, decades of cost shifting in all likelihood have contributed to less disciplined decision making in health care.

Using the findings of their research, Intermountain’s finance team set out to build more rationality into their organization’s capital process.

Make Evaluations More Strategic

Health systems too frequently view capital investments as one-time decisions based on what they can afford at any particular time. Leaders at Intermountain are committed to a different tack. They review all proposed investments within a larger strategic context to determine whether the investments are the best use of resources for the long term. In the case of a new facility, for instance, that time frame should be at least 40 years. To make their review process more forward-focused, Intermountain’s leaders implemented several strategies that they borrowed from other industries, and developed others on their own.

- Does the investment result in appropriate access to (or utilization of) care?

- Does the investment result in demonstrable benefits of high quality and/or service excellence without compromising affordability?

- Is the investment consistent with appropriately aligned incentives and improved engagement?

- Does the proposal have a well-defended, evidence-based business case?

- Does the investment have manageable risk?

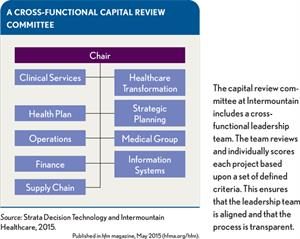

A Cross-Functional Capital Review Committee

Using forward-thinking evaluation criteria. The capital review committee assesses proposals based on five evaluation criteria, which have been refined over the past few years:

Although all questions are critical, the second question is especially meaningful because it helps the committee focus on the quality and cost of care. Too often, the industry has adopted technologies or added capacity that have come with significant cost increases, but provided little to no benefit. Similarly, the third question helps weed out investments such as unnecessary imaging equipment that accommodates additional volume but that may not reflect Intermountain’s broader goal of eliminating unnecessary utilization.

Employing utilization benchmarks. Intermountain’s leaders leverage the health system’s enterprise data warehouse (EDW) and cost-accounting system to make informed capital decisions across the organization. For example, they continue to establish utilization benchmarks to ensure they are delivering the right level of services to support their population without producing excess capacity that could create an incentive to deliver unnecessary care. Analysts are building capabilities to take a hard look at data trends to determine the appropriate number of elements such as operating rooms, CT scanners, linear accelerators, and even providers in their community. The capital review committee is charged with evaluating these benchmarks to either filter out proposals prior to formal review or to use as key data points as decisions are being made.In addition, Intermountain’s strategic-planning, healthcare transformation, and finance teams are working to update and improve their facility- leveling methodology. These resources help proposal leaders determine the appropriate intensity and mix of services for a given facility, based on its size and demography. Combined with utilization benchmarks, these templates help ensure that operations leaders and decision makers carefully weigh the services they plan to offer.

- What strategic need would this project meet, and what is the ultimate objective (e.g., clinical, regulatory, efficiency, compliance, security)?

- How will appropriate utilization be achieved and/or maintained?

- How will this project create system cost savings or increased value for patients and plan members?

- How will this project affect access to care?

- What risks does the organization face if it does not proceed with this project?

Creating relevant templates for strategic plans. Another valuable template created by Intermountain’s finance team is the five-year plan for major project proposals. The multipage template requires project leaders to answer the following key questions:

The template was designed to help leaders think more strategically about the potential impact of their proposal on the broader goals and direction of the organization.

Set Aside the Old Pro Formas

As healthcare organizations take on more risk, they should move beyond the pro formas of the past and select a financial model that provides a more accurate assessment of the impact of value-based payment arrangements.

In early 2014, finance leaders initiated a collaboration with leaders from Intermountain’s health plan, strategic planning group, and healthcare transformation team to rebuild their analytical model. Rather than relying on a pro forma based on volume to arrive at a net present value, the cross-functional team has developed a new approach that compares various financial scenarios. The number of scenarios depends on the specific circumstances, because the scenarios are tailored to each situation. The scenarios are based on viable alternatives to a given problem and analyzed based on economic impacts in a value-based payment framework. Specifically, the model considers cost avoidance, market penetration, operational efficiencies, and other outcomes to help calculate which scenario brings the most overall value to Intermountain’s constituency.

Finance leaders have tested the model and are implementing it across the health system. Proposal champions have responsibility for ensuring that the financial analyses are conducted pragmatically and account for current strategies and future payment methodologies. Local teams coordinate with corporate finance to arrive at assumptions and approaches. For example, corporate experts help proposal leaders determine which scenarios they should include in their modeling. Once the modeling is complete, the corporate finance team reviews it, challenges assumptions, and makes changes as appropriate.

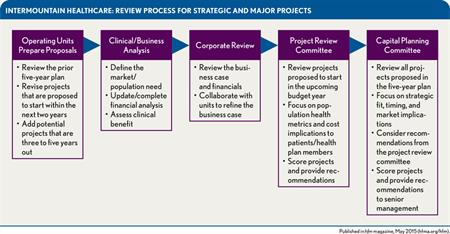

Intermountain Healthcare: Review Process for Strategic and Major Projects

Shed Light on Large Projects

Breaking larger projects into smaller components for greater transparency has become a best practice at Intermountain. Finance leaders review analyses of large, complex projects to remove unnecessary components. Historically, projects may have been approved at a macro level without careful consideration of the individual components, with the result that elements that should have been scrutinized were effectively buried in the broader proposal. Recent examples of the more granular approach are decisions by finance leaders to exclude unnecessary imaging equipment and superfluous rehabilitation pools from recent construction projects because the anticipated level of use did not justify the cost burden.

Reviewing large projects at a more granular level also gives health system leaders an opportunity to enhance services, including those that might not have provided financial value under a volume-based revenue model. For example, Intermountain leaders have added low-acuity urgent care centers to several of their hospital expansion projects. Under a traditional model, such centers would not be financially beneficial because revenue would be pulled from the emergency department. However, Intermountain leaders view these centers as critical to helping patients receive the right level of care for their needs-and controlling costs under risk-sharing models. Similarly, system leaders have added wellness centers to recent projects because of their complementary role in managing a population’s health.

Make the Release of Funds More Rigorous

Once projects are approved and budgeted at Intermountain, the health system’s finance team closely manages the funds to ensure resources are used appropriately. Funds for any project of $250,000 or greater must be formally authorized by the health system’s CFO and COO before any purchase can be made. Each quarter, the finance team presents a list of upcoming funds for budgeted projects to the CFO and COO. This approach allows C-suite leaders to manage cash flow or stop funding if circumstances have changed since the project was approved.

As an added monitoring step, the finance department links its capital- budgeting solution with its enterprise resource planning (ERP) software. Finance staff use the budgeting program to develop their budgets, which are then fed into the ERP tool. As expenditures are made against budgeted projects, the ERP software sends data back into the cost-accounting tool to keep track of capital pools in real time. Projects with funding of $250,000 or greater are tracked at the corporate level, while smaller projects typically are managed at the local level.

Treat Look-Backs as a Learning Tool

To make more informed decisions, Intermountain’s leaders have developed a comprehensive look-back process. Each year, the health system’s finance team selects roughly 40 funded projects for possible review. These projects are typically strategic in nature and must have been completed in the previous 36 months. With criteria such as applicability to future investments or measurement of operational success in mind, the health system’s senior executives score each project to determine the most worthwhile eight to 10 projects to review that year.

During the look-back, the finance team reviews past performance and reworks forecasts to determine whether leaders need to make midstream corrections or adjust funding for similar projects underway. Once completed, the team presents the results to the board’s finance committee. As a result of this comprehensive look-back process, clinical and operational leaders tend to approach their analyses more thoughtfully, knowing that their forecasts may be under board scrutiny in three or four years.

A More Accountable Future

Intermountain’s leaders have recently approved several large capital projects that support the health system’s move into population health- including projects that might not have been as compelling in prior years. For example, they recently approved the addition of a 75,000-square- foot specialty clinic that brings together various specialists in a team-based care delivery model. And for good reason: Early data from similar Intermountain clinics suggest that placing complementary providers in a team setting can reduce ED visits, curb inpatient admissions, improve medication compliance, and increase primary care visits. The model also drives operational efficiencies. Intermountain’s leaders have striven to align their incentives and recognize that driving down costs for payers and patients while improving outcomes is the right thing to do.

As part of their capital decision-making process, the leaders are careful to fund proposals that truly meet community need. Behavioral health, a service line that is not profitable for most healthcare organizations, is a good example. Intermountain continues to integrate mental health services into its team-based care approach to help improve the health of the community and drive down the total cost of care.

Although future-leaning capital investments might not always yield short-term financial benefits, Intermountain Healthcare’s leaders believe disciplined capital decisions will contribute to long-term success. As payment models evolve, an objective capital process will be critical for leaders to recognize strategic opportunities, enhance ongoing operations, and maintain sustainable growth while investing resources wisely.

Clay Ashdown is assistant vice president, financial planning and capital investment, Intermountain Healthcare, Salt Lake City.

Lynette Jasuta is director of consulting service, capital planning, Strata Decision Technology, Chicago, and a member of HFMA’s First Illinois Chapter.