Park Nicollet Health Says Goodbye to the Line-Item Budget

May 27, 2015

The line-item budget, an age-old financial planning tool, is no longer welcome at Park Nicollet Health Services in St. Louis Park, Minn. Since 2006, Park Nicollet has used a rolling financial monitoring and forecasting process that eliminates much of the minutiae of preparing a yearly revenue forecast and allocating expenses across it.

Today the health system uses a model of continuous improvement—one derived from the so-called Lean culture model— in which departments are simply expected to do better than the previous year.

B.J. Miller, senior director of performance and planning at Park Nicollet, says the model helps the system deal with the current economic environment.

“We have about $20 to $25 million in margin deterioration annually because of macro factors and expense inflation,” he says. “We either have to grow or become more productive or more efficient, or we will lose ground.”

Margin Improvement

The new approach replaces budgetary line-item fixation with a process driven by regular reviews of department performance. “Conventional budgets,” Miller observes, “are burdened with detail that explain how much you are spending on administrative supplies, on continuing education, on salaries, on benefits, on categories of FTEs. You end up trying to guess the future and, when it arrives, explaining why your guess was wrong.

“We don’t do any of that,” he continues. “We avoid a lot of that detail. We work under the assumption that this year and next year will be similar, so we just look at the bottom line. What is your direct margin?”

Park Nicollet divides its financial planning into six service lines: primary care, specialty services, surgery, inpatient treatment, behavioral health, and support areas, such as human resources and IT. Each department is expected to show improved margins year to year.

“We set an incremental growth target,” Miller explains. “You have to improve every year. If you did $84 million last year, let’s shoot for $85 million. We won’t let you slide back to $80 million. It is a hard argument to make that we should be allowed to do worse. There may be some exceptional circumstances, but then you have to ask ‘How will we minimize the damage.’”

Different Pressures

Although department leaders cheered the idea of being freed from writing detailed budgets, they have faced new challenges in the continuous growth model.

“Our approach puts a different level of pressure on department leaders,” Miller says. “It is a different expectation and skill set. We want people to think and reflect about what is happening in reality. We don’t want them to follow a budget on autopilot. In real time, they have to ask themselves: ‘Why do we need to hire three FTEs?’”

But department leaders do not work in a data vacuum. They have access to a financial reporting and forecasting software that the finance department uses. Using the software, the financial team enters assumptions about future volumes, staffing levels, and expense inflation. The software then calculates the metrics with projections across time, which helps the finance team and operational leaders keep tabs on performance.

“It helps impose some discipline on us to do the monitoring more regularly,” Miller says.

Regular Meetings with Service Line Leaders

“In cardiology, if the number of cath procedures is growing and resulting in less open heart procedures, we will discuss how to react,” Miller says.

At the meetings, department and finance leaders focus on just a handful of metrics:

> Volume (measured by encounters, procedures, or admissions)

> The number of physicians/clinicians

> The number of support staff

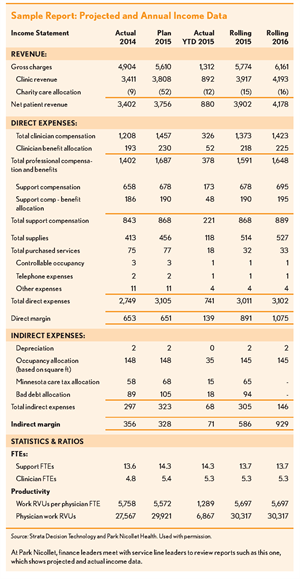

Miller’s team converts the volume to revenue and the FTEs to salary expenses. All the data—consolidated by the forecasting software—is then fed back to the departments (see the exhibit).

“Conventional budgets are burdened with detail that explain how much you are spending … You end up trying to guess the future and, when it arrives, explaining why your guess was wrong.”

Monthly performance monitoring is led by a senior strategist and an assisting analyst who support all of the departments in a service line. The surgery service line, for example, has some

20 sub-specialty departments, each of which has its own performance targets. This approach leads to a lot of meetings— with 80 departments across the organization—but reinforces the importance of monitoring performance and adapting to market realities, Miller says.

In addition to monthly department meetings, Miller’s team sets up quarterly review sessions with each service line to monitor performance at that level.

“We can feed back their volume assumptions and see how that translates to dollars on both the revenue and expense side,” Miller says. “If their margin is improving, they get a lot less scrutiny than if not.”

Clinical Leaders as Business Owners

The payer mix is a big factor in overall performance—and right now, it is working against the health system, Miller says. “If last week you came in for treatment at age 64, and then next week you come back at 65 for the same service, our revenue will go down 40 percent because you are on Medicare.”

Miller estimates the annual impact of patients leaving a commercial plan and going on Medicare is as much as $8 mil- lion. “We have to work with our operational leaders to figure it out. If they keep the same staff and same volumes, their performance will get worse.”

Against that backdrop, Miller says the biggest challenge in transitioning to the no-budget approach is the lack of business training among department leaders. Many rose through the ranks as clinical caregivers.

“Rather than just manage expenses, they have to run a business. But understanding the financial implications of your choices is more intuitive for finance leaders than clinically trained operation- al leaders. We have to help operational leaders understand the financial impact of their month-to-month and even their hour-to-hour decisions,” he says.

For example, if the department has no more patients scheduled at some point late in the day, it behooves the manager to send staff home early. “It hurts the person who gets their check cut by 15 minutes, but if we let everybody stay with no reason, we spend ourselves to a bad position,” Miller observes.

Miller says the training includes class- room time during the on-boarding process that introduces new managers to the overall financial picture and the metrics they should use. On-the-job training and follow-up occur as needed.

Lessons Learned

Miller has some advice to others contemplating the move to this type of system.

First, it’s important to make sure the entire executive team is in agreement with the change, he says. Unity in the C-suite is vital.

Second, be prepared to adapt. He says it’s more important to flexibly deal with challenges as they arise than to set hard goals and struggle to meet them. “It’s not as much about setting numbers in the beginning of the year than it is reacting to unforeseeable changes and adapting to them,” he says.

Finally, don’t be overly concerned about details in the planning stage. “The details can be dealt with in the day-to-day and weekly decisions,” he says. “There are too many things you won’t know about in the beginning.”

Stable Finances

Miller says the new system has been well adopted by the staff, and today they are more aware of the financial impact of operational decisions. The health system has had a stable margin since 2009, which he attributes to the staff’s conscious effort to adapt to economic realities.

At the same time, there are still challenges, he acknowledges. “When you tell people they can’t do worse than last year, they get that. But making it happen is hard. People who need the most help are sometimes the most frustrating to educate. Our finance team has to take the time to get everybody up the learning curve.”

Frank Stevens is vice president of financial planning at Strata Decision Technology, Chicago (fstevens@ stratadecision.com).

Interviewed for this article: B.J. Miller, senior director of performance planning, Park Nicollet Health Services, St. Louis Park, Minn.